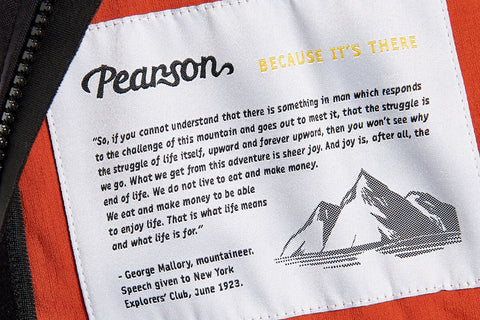

Always Read the Label: Because It’s There

Whether riders or rock-climbers, the mountains have called adventurers for generations. Pearson’s Adventure collection raises a glass - champagne, naturally - to an icon of exploration.

When you’ve been around as long as Pearson has, that’s a lot of history. A lot of wandering off the map. A lot of firsts. We like to think of that history as a palette of influences, upon which adventurous souls shine brightest. Comprising bikes and clothing, the Pearson Adventure collection has been designed for those pioneering spirits who look at their GPS and say not, “Too far”, but, “Let’s go”. One such figure was George Mallory, the man who just might along with partner Andrew ‘Sandy’ Irvine, have been first to the summit of Mount Everest in 1924 that is, 29 years before Sir Edmund Hillary’s confirmed first ascent, on 29th May 1953. The debate still simmers, although the accumulative evidence of intervening years has deemed Mallory’s success less likely.

George Mallory, whose exploits are celebrated in Pearson’s upcoming Adventure Long Sleeve Jersey remains an enigmatic, elusive figure. Born in 1886, the son of a Cheshire vicar, he was a climbing prodigy even as a child, scaling all manner of obstacles with feline ease. On one occasion when sent to his room in 1873 he escaped from the window to climb, so legend has it, the church spire. He was seven years old.

School was Winchester College, then on to Cambridge where he read history and encountered a rich and progressive intellectual landscape. He joined the Fabians, championed female suffrage and began to favour agnosticism over the Christian doctrine of his childhood. His circle included Geoffrey Keynes, the future surgeon and author, and the poet Rupert Brooke. Mallory also befriended members of the Bloomsbury set, centred on the flamboyant writer, Lytton Strachey. For Strachey the imposing and muscular Mallory was an exotic flower in bookish company, a gift from Mount Olympus to progressive intellectuals steeped in the Classics. “[Mallory has] the body of an athlete by Praxiteles [a renowned Athenian sculptor],” swooned Strachey, “and a face — oh incredible — the mystery of Botticelli, the refinement and delicacy of a Chinese print, the youth and piquancy of an unimaginable English boy.”

It was at Cambridge that Mallory fell in with a celebrated mountaineer of the age, Geoffrey Winthrop Young. It was Young who noted, on a climbing trip to Wales, how gracefully Mallory moved over rock faces. “Whatever may have happened unseen… between him and the cliff, in the way of holds or mutual adjustments,” wrote Young, “the look, and indeed the result were always the same — a continuous undulating movement so rapid and powerful that one felt the rock must either yield or disintegrate.”

For Mallory, climbing was a physical corollary to the intellectual life he enjoyed elsewhere. Having served on the western front he returned to England deeply troubled by the carnage he witnessed in the trenches. Climbing proved his salvation. Until 1852 the highest point on the planet was believed to be Nanda Devi, that mountain in the northern Indian Himalayas which stands at 25,479ft. The Great Trigonomic Survey of India 50 years in the making concluded the title belonged to another peak, Mount Everest at 29,035ft more than 4,000ft higher than Nanda Devi. Mountaineering’s golden age was only just getting started. Though Mont Blanc at 15,774ft the highest peak in western Europe was first scaled in 1786, it would be another 81 years in 1865 before a successful ascent of the technically challenging Matterhorn (14,692ft).

Compared with Everest, however, these were foothills. By the survey’s conclusion in 1852 no western climber had come close to even the base of Everest, let alone its summit. The Alpine Club, Britain’s national body for ‘alpinism’, had been established in 1857 but it was not until its 50th anniversary in 1907 that calls for a British expedition to Everest began to gather momentum.

It became a matter of national pride. In 1909, America’s Robert Peary had been first to the geographic North Pole in 1911, Norway’s Roald Amundsen beat Britain’s Robert Falcon Scott to its southern counterpart. The outbreak of war put a check on British ambitions until in 1919 the president of the Royal Geographical Society, Sir Francis Younghusband, announced plans for a British assault on Everest. Younghusband had experience of expeditions to remote locations; in addition to supporting Scott, the RGS had aided Charles Darwin — during his five-year voyage around the world aboard HMS Beagle — and David Livingstone in Africa.

George Mallory was involved in three expeditions to Mount Everest, all to the northern side of the mountain in Tibet. The first in 1921 did not reach the summit but found a hitherto undiscovered route, through the Rongbuk Glacier. This allowed Mallory to climb as high as the North Col, today a key point on the summit route, at 23,000ft. During a second expedition a year later Mallory was 600ft short of the North Col when an avalanche swept his team of Sherpas to their deaths, forcing the expedition to be abandoned.

But it is the expedition of 1924 which cemented the Mallory legend. The expedition arrived at base camp on 29th April 1924 and dined on quails’ eggs, foie gras and champagne. It proved a brief, pleasurable hiatus. Over the coming weeks the weather repelled them repeatedly until eventually they were able to establish their higher camps above the North Col; Camp V at 25,500ft and a further base, Camp VI, at 28,800ft. Mallory accompanied by Sandy Irvine made his summit bid on 8th June 1924 in a state of indecent haste. He had already sent a cooker tumbling down the mountain and entirely forgot his compass. Some way below a colleague Noel Odell was waiting to capture the moment on film. At around 12.50pm, the gathering clouds parted, briefly, to reveal two black spots high on the mountain’s shoulder. Odell was the last person to see either man alive. Mallory’s body was eventually found 75 years later by the American climber Conrad Anker.

The body of Sandy Irvine remains entombed, perhaps on flanks of the great peak, or in some deep crevasse. Such clues as might confirm Mallory was first to the top seem fanciful; a missing camera for example whose undeveloped film could contain a summit photograph. Evidence that conditions were likely to have gone against him on the other hand feels robust. One theory proposes that a ‘false summit’ some distance from their ultimate target, may have deceived Mallory into pressing on when dwindling oxygen supplies should have cautioned otherwise.

Whatever the outcome, George Mallory was a true and brave pioneer and we at The 1860 salute him. As he told an audience at the New York Explorers’ Club in 1923: “If you cannot understand that there is something in man which responds to the challenge of this mountain and goes out to meet it, that the struggle is the struggle of life itself, upward and forever upward, then you won’t see why we go.” Or, as he famously put it, when asked why he was so determined to answer the siren call of Everest: “Because It’s There.”