Sustainable cycling and the next generation

Christmas is a time for family, and Pearson 1860 has been a family cycling business for 160 years. Now in the hands of a fifth-generation, we hope future Pearsons will continue our mission, to get more people cycling and produce the most sustainable bikes and kit. Yet as history shows, keeping things in the family can be fraught with risk.

The generations game. Guardian newspaper, the journalist Ian Sansom profiled numerous dynasties; politicians, monarchs, musicians, artists and sports stars. In some fields, such as banking, there were too many to number. "The Barings never got a look in," Sansom wrote in his final entry, “or the Fords, or the Gettys”. The sorts of names, in fact, who make dynasties seem archaic. But plenty are still around and, as the recent HBO smash 'Succession' suggests, their manoeuvrings and machinations still have the capacity to enthral.

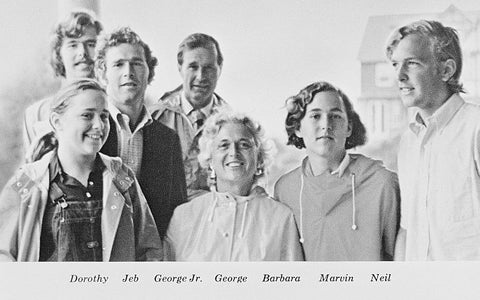

In the US, for example, the Bush family is prominent in both business and politics. Two Bush boys have served terms as US presidents, most recently George 'Dubya', from 2001 to 2009, and before that his father, George Herbert Walker (1989–1993). George junior’s brother, Jeb, served as the governor of Florida from 1999 until 2007, and was himself briefly, in 2015, a Republican candidate for the top job. Campaigns cost money, of course, and the Bush dynasty fills its coffers through banking and oil. Regular dealings with Saudi Arabia have netted a fortune well north of $60m.

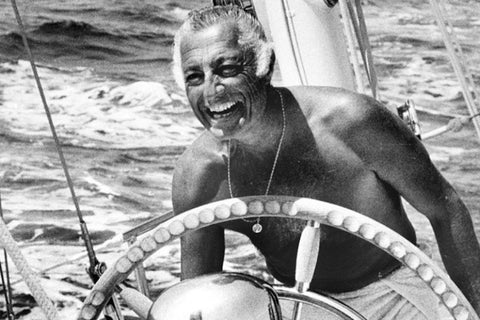

In Europe, the Agnellis trace their commercial lineage back to 1889, when the original company was formed. (Not quite as old as Pearson but good effort.) Italians liken them to the Kennedy clan, and it’s hard to deny they have a certain glamour. They own Ferrari, Juventus football club and are majority shareholders in automotive giant, Fiat. With a fortune likely to run to billions of dollars, the current torchbearer is the distinctly un-Italian sounding John Elkann. (Also, the fifth generation to steer the family ship.)

Well up down under. In the southern hemisphere, a leading dynasty is that headed by Rupert Murdoch, the tycoon whose media empire is as prominent in Britain and America as it is in his native Australia (and was the inspiration for ‘Succession’). It was Rupert’s father, Keith, who founded the business, first acquiring newspapers, in the 1920s. In subsequent decades, Murdoch the Younger’s News Corporation has, through his abrasive deal-making, expanded to include television stations, such as Sky and Fox News.

His stranglehold on traditional print media has loosened as that sector has declined, but he still owns The Times and The Wall Street Journal. The Murdoch family is estimated to be worth around $14 billion. (American, not Aussie.) Rupert’s children feature prominently. His son, James, is in charge of 21st Century Fox, while Rupert’s daughter, Elizabeth, has occupied numerous high-profile positions, notably in broadcasting interests.

There can, inevitably, be downsides. Sansom concluded his series by highlighting something known as the ‘Buddenbrooks’ effect. The term is derived from the novel Buddenbrooks, by Thomas Mann, published in 1901. It charts the fortunes of the eponymous dynasty, who build a vast fortune selling a superior brand of mousetrap. The story thereafter is one of decline, an oft-cited exemplar of how and why dynasties crumble. Problems arise for the Buddenbrooks when they take the technology as far as they can. When their customers have all the mousetraps they need, the business, now under a new generation, stagnates. The killer blow is delivered by the third generation, who have no interest in the mousetrap game, blow their inheritance, then asset-strip the family business in search of cash.

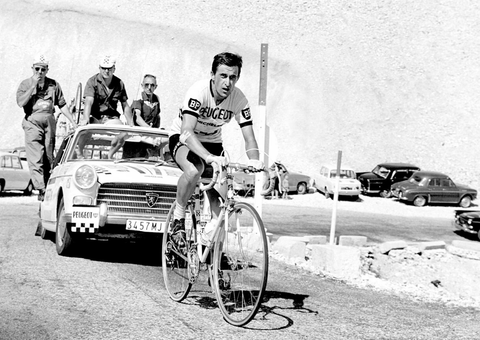

The girls from the black stuff. So how to guard against wayward scions? Sansom cites the economist David S. Landes, who in turn references the rules applied by Robert Peugeot, of the French car-manufacturing dynasty (and once ardent sponsor of French cycling). “Shares in the enterprise would be passed only to sons,” Monsieur Peugeot advises, “never to daughters or sons-in-law.” Black sheep, Peugeot believed, had to be buried (not literally) where they couldn’t make trouble. One way of avoiding the Buddenbrooks’ effect, perhaps, although hardly the attitude of a modern CEO.

The Guinness clan, in Ireland, offer a variant on Peugeot’s dictum; historically, the men have controlled the brewing empire, while the women made the headlines. Fabulously well-connected, the Guinness girls have long fascinated the popular press, starting with the daughters of Arthur Guinness, the firm’s founding father; of his three girls, Aileen, Oonagh and Maureen, the latter was notoriously mischievous. “The sisters are all witches,” wrote the film director John Huston. "Lovely ones to be sure, but witches nonetheless."

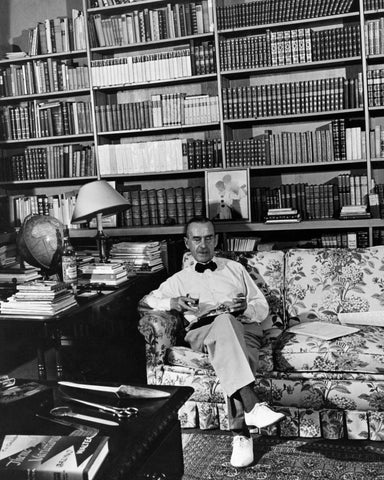

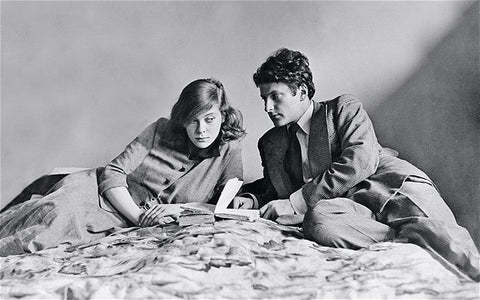

Catherine Blackwood sandwiched Bacon between Freud and Lowell.

Maureen went on to become something of a social climber, neglecting her daughters, or so they claimed. One, Lady Catherine Blackwood, eloped with the painter Francis Bacon. Described in an obituary (she died in 1996) as “petite and delicate in looks, but gauche and eerie in spirit”, Catherine moved on, to the poet Robert Lowell, and also wrote a Booker-nominated novel. Tragedy, however, seemed to dog the family. Catherine’s daughter, Natalya, died in 1978, aged just 18; a cousin, Henrietta, committed suicide in Italy. But the money remains, most prominently in the form of Daphne Guinness, a high-profile personality.

Blood money. It is fashionable, not least in Republican circles, to depict wealthy families as de facto monarchs. There are caveats, of course; take Nancy Mitford’s famous riposte to the Guinnesses being likened to Ireland’s royal family. "An aristocracy in a republic is like a chicken whose head has been cut off,” Mitford wrote. “It may run about in a lively way, but in fact it is dead."

Unlike the Buddenbrooks, we at Pearson don’t think we’ve done as much as we can to advance the humble mousetrap, or in our case the humble bike. We like to think we’re not headless chickens (not all the time) and that we are always looking to improve. Our dynasty, such as it is and modest in comparison to some mentioned here, creates bikes that are a pleasure to own and ride, and will be for many years to come.

For more on the Pearson story: About Us